重点!呼吸道传染病R0之初探(建议收藏)

(来源:HEALTH LAB)

每种传染病都有其不同的传染性,根据这一特性,科学家通过R0这项关键指标衡量病毒传染性。

基本传染数(basic reproduction number, R0),又称基本再生数,指所有人对某个传染病都易感且没有外力干扰的情况下,一个感染者能把疾病传染给其他人数量的平均值,是疫情早期衡量传染病传播速度的重要指标。

在一个完全易感人群中持续输入,且没有采取防控措施的地区内:

当R0>1时,表示1个感染者能传染>1个人,疾病将发生流行;

当R0<1时,表示1个感染者在其传染期内感染人数<1个人,疾病逐渐消失。

也就是说,R0越大,表示疾病的传染能力越强。

2020年3月12日,世界卫生组织(WHO)正式宣布将新型冠状病毒肺炎(coronavirus disease 2019,COVID-19)列为全球性大流行病,截至2021年3月05日,共有223个国家和地区报告超过1.15亿确诊病例,其中死亡人数已高达255万人。新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的R0=2.5;这是21世纪以来人类经历的第二次传染病大流行,上一次是2009年由新型甲型H1N1流感病毒所引发的大流行,据美国CDC统计,甲型H1N1流感病毒(2009)引起的全球死亡人数为14-58万人,单从死亡人数来看比新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)传染能力略低,其流感(2009 pandemic strain)的R0=1.2-1.6。而在1918年流感大流行是最近历史上最严重的大流行,据美国CDC预计当年的感染人数高达世界人口的三分之一,其中死亡人数高达5000万!流感(1918 pandemic strain)的R0=2-4,因此被誉为迄今为止最致命的大流行。

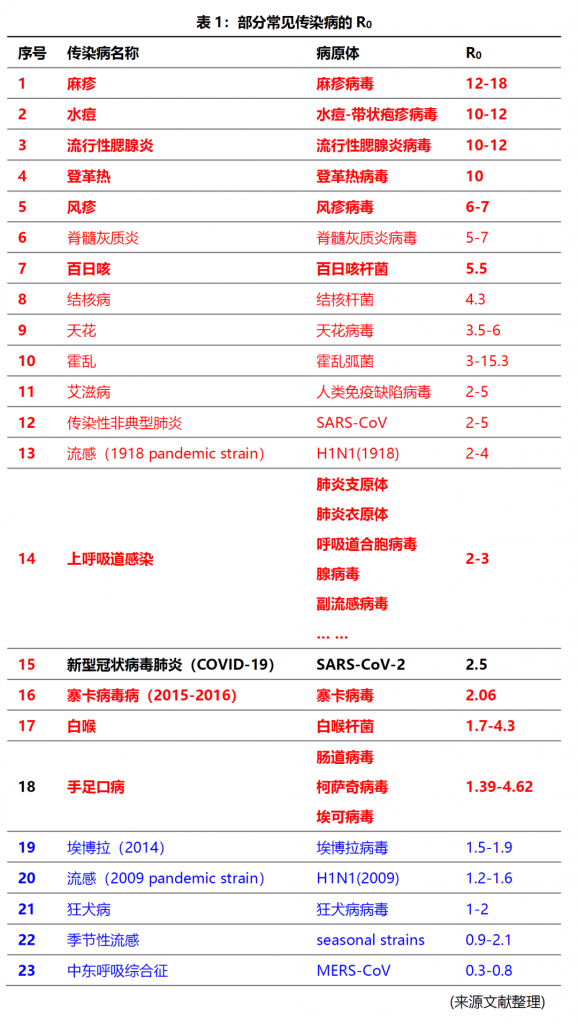

除了以上的新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)和流感大流行以外,小编还通过搜索国内外相关研究文献,整理部分常见传染病的R0,内容仅供参考(详见表1);从表1中可以看出,在R0>1的传染病中,麻疹,水痘、流行性腮腺炎、登革热、风疹、脊髓灰质炎、百日咳、结核病、天花、霍乱、艾滋病、SARS、流感、上呼吸道感染、寨卡病毒病、白喉、手足口病的传染性均强于COVID-19;

麻疹的传染性最强,是新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的6倍;

水痘、流行性腮腺炎是新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的4.4倍;

登革热是新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的4倍;

风疹、白喉是新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的3倍;

百日咳、结核病、手足口病是新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的2倍;

艾滋病是新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的1.5倍;

上呼吸道感染(肺炎支原体、肺炎衣原体、呼吸道合胞病毒、腺病毒、副流感病毒等)、流感(1918 pandemic strain)是新型冠状病毒肺炎(COVID-19)的1-1.5倍;

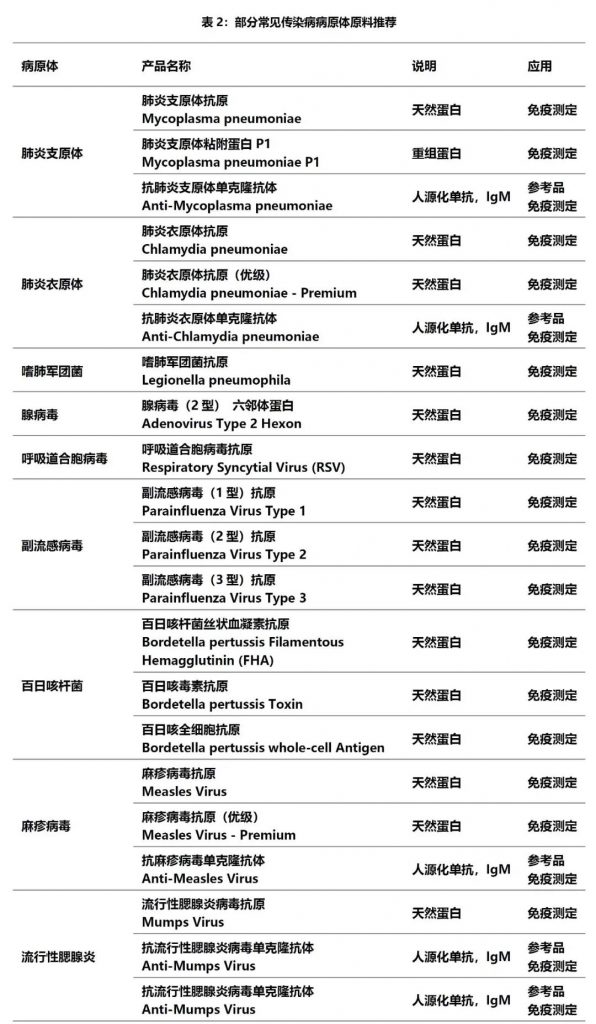

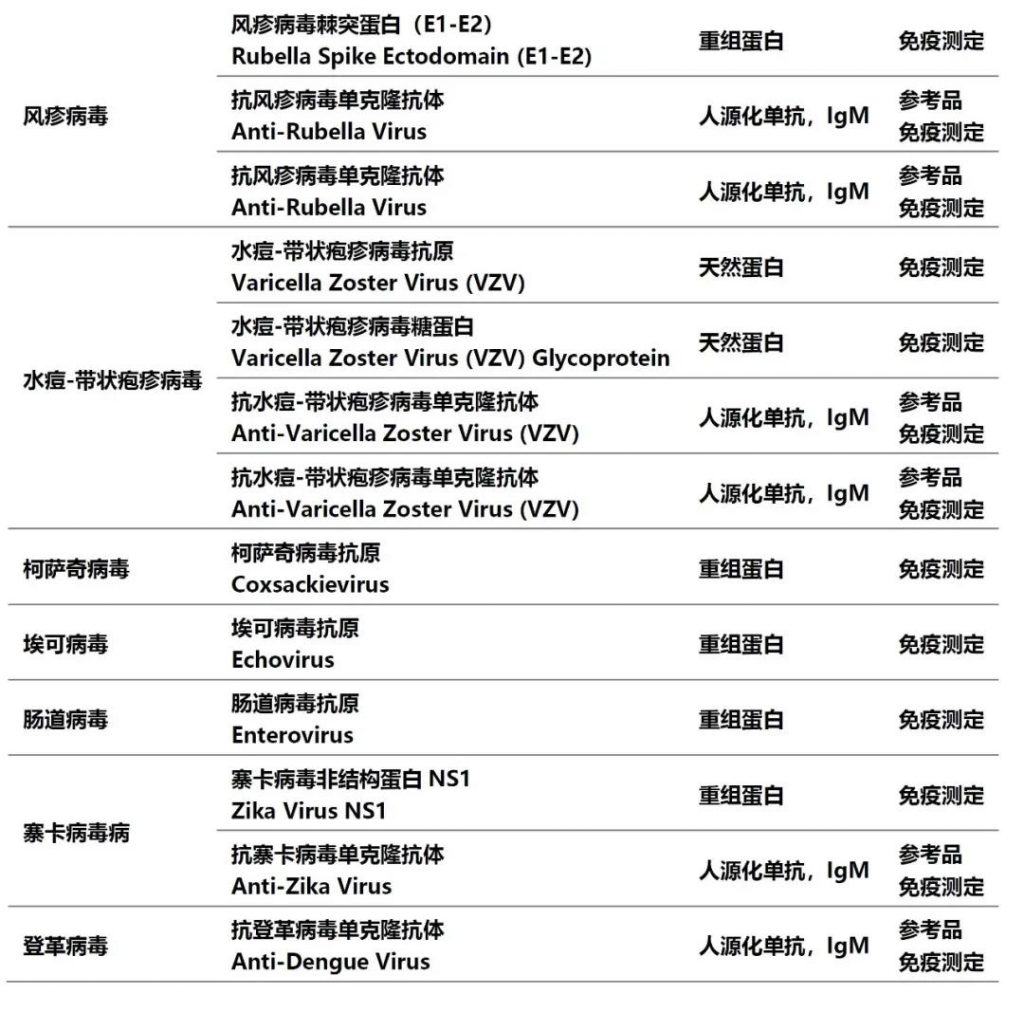

在表1中部分常见的传染病70%以上均通过呼吸道系统感染,在新型冠状病毒肺炎后疫情时代,对传染病的防控,尤其是对这些传染性极强的疾病予以重视;而针对这些疾病的检测在社区传播和院内感染防控中发挥着重要作用。德国维润赛润涵盖多种病原体系列原材料,包括天然抗原、重组抗原和人源化单抗,助力常见传染病检测项目的开发(见表2)。

1. Guerra, Fiona M.; Bolotin, Shelly; Lim, Gillian; Heffernan, Jane; Deeks, Shelley L.; Li, Ye; Crowcroft, Natasha S. (December 1, 2017). “The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review”. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 17 (12): e420–e428.

2. Ireland’s Health Services. Health Care Worker Information (PDF). Retrieved March 27, 2020.

3.Australian government Department of Health Mumps Laboratory Case Definition (LCD)

4. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; World Health Organization (2001). “History and Epidemiology of Global Smallpox Eradication”. A module of the training course “Smallpox: Disease, Prevention, and Intervention”. Slide 17. This gives sources as “Modified from Epid Rev 1993;15: 265-302, Am J Prev Med 2001; 20 (4S): 88-153, MMWR 2000; 49 (SS-9); 27-38”.

5. Eisenberg, Joseph (February 12, 2020). “R0: How Scientists Quantify the Intensity of an Outbreak Like Coronavirus and Its Pandemic Potential”. sph.umich.edu. Retrieved September 4, 2020.6. Kretzschmar M, Teunis PF, Pebody RG (2010). “Incidence and reproduction numbers of pertussis: estimates from serological and social contact data in five European countries”. PLOS Med. 7 (6): e1000291.

7. Gani, Raymond; Leach, Steve (December 2001). “Transmission potential of smallpox in contemporary populations”. Nature. 414(6865): 748–751. doi:10.1038/414748a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11742399. S2CID 52799168. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

8. Prather KA, Marr LC, Schooley RT, et al. (October 16, 2020). “Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2” (PDF). Science. 370 (6514): 303–304. doi:10.1126/science.abf0521. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

9. Sanche, S.; Lin, Y. T.; Xu, C.; Romero-Severson, E.; Hengartner, E.; Ke, R. (July 2020). “High Contagiousness and Rapid Spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2”. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 26 (7): 1470–1477.

10. “Novel Corona virus – Information for Clinicians” (PDF). Australian Government – Department of Health. July 6, 2020.11. “Playing the Numbers Game: R0”. National Emerging Special Pathogen Training and Education Center. Archived from the originalon May 12, 202. Retrieved December 27, 2020. […] while infections that require sexual contact like HIV have a lower R0 (2-5).

12. Freeman, Colin. “Magic formula that will determine whether Ebola is beaten”. The Telegraph. Telegraph.Co.Uk. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

13. Chowell G, Castillo-Chavez C, Fenimore PW, Kribs-Zaleta CM, Arriola L, Hyman JM (2004). “Model parameters and outbreak control for SARS”. Emerg Infect Dis.

14. Clinical and Epidemiological Aspects of Diphtheria:A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis.

15. Ferguson NM; Cummings DA; Fraser C; Cajka JC; Cooley PC; Burke DS (2006). “Strategies for mitigating an influenza pandemic”. Nature. 442 (7101): 448–452.16.Khan, Adnan; Naveed, Mahim; Dur-e-Ahmad, Muhammad; Imran, Mudassar (February 24, 2015). “Estimating the basic reproductive ratio for the Ebola outbreak in Liberia and Sierra Leone”. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 4: 13.

17. Fraser, Christophe; Donnelly, Christl A.; Cauchemez, Simon; Hanage, William P.; Van Kerkhove, Maria D.; Hollingsworth, T. Déirdre; Griffin, Jamie; Baggaley, Rebecca F.; Jenkins, Helen E.; Lyons, Emily J.; Jombart, Thibaut (June 19, 2009). “Pandemic Potential of a Strain of Influenza A (H1N1): Early Findings”. Science. 324 (5934): 1557–1561.

18. Coburn BJ; Wagner BG; Blower S (2009). “Modeling influenza epidemics and pandemics: insights into the future of swine flu (H1N1)”. BMC Medicine. 7. Article 30.

19. Kucharski, Adam; Althaus, Christian L. (2015). “The role of superspreading in Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) transmission”. Eurosurveillance. 20 (26): 14–8. 20. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infection[M].2004.

20. Prof Eskild Petersen,Comparing SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV and influenza pandemics. The Lancet infectious Diseases. 2020.

21. Application of a Mathematical Model inDetermining the Spread of the Rabies Virus: Simulation Study.

22.Quantifying TB transmission: a systematic reviewof reproduction number and serial interval estimates for tuberculosis.

23.Estimating the basic reproduction rate of HFMDusing the time series SIR model in Guangdong, China.